[ARC-AGI-2 SoTA] Efficient Evolutionary Program Synthesis

or: How I Broke the Efficiency Frontier With a DreamCoder-inspired Approach

In a world of impressive AI results (IMO Gold; 88.1% on Graduate-level STEM questions; 74.9% on Software Engineering tasks), one benchmark is still unsaturated. Abstract and Reasoning Corpus for Artificial General Intelligence (ARC-AGI), which was originally introduced by François Chollet in On the Measure of Intelligence, remains a challenge that humans perform well on while machines struggle. On ARC-AGI-2, the second generation competition with a $1 million in prizes, no frontier models score above 16%.

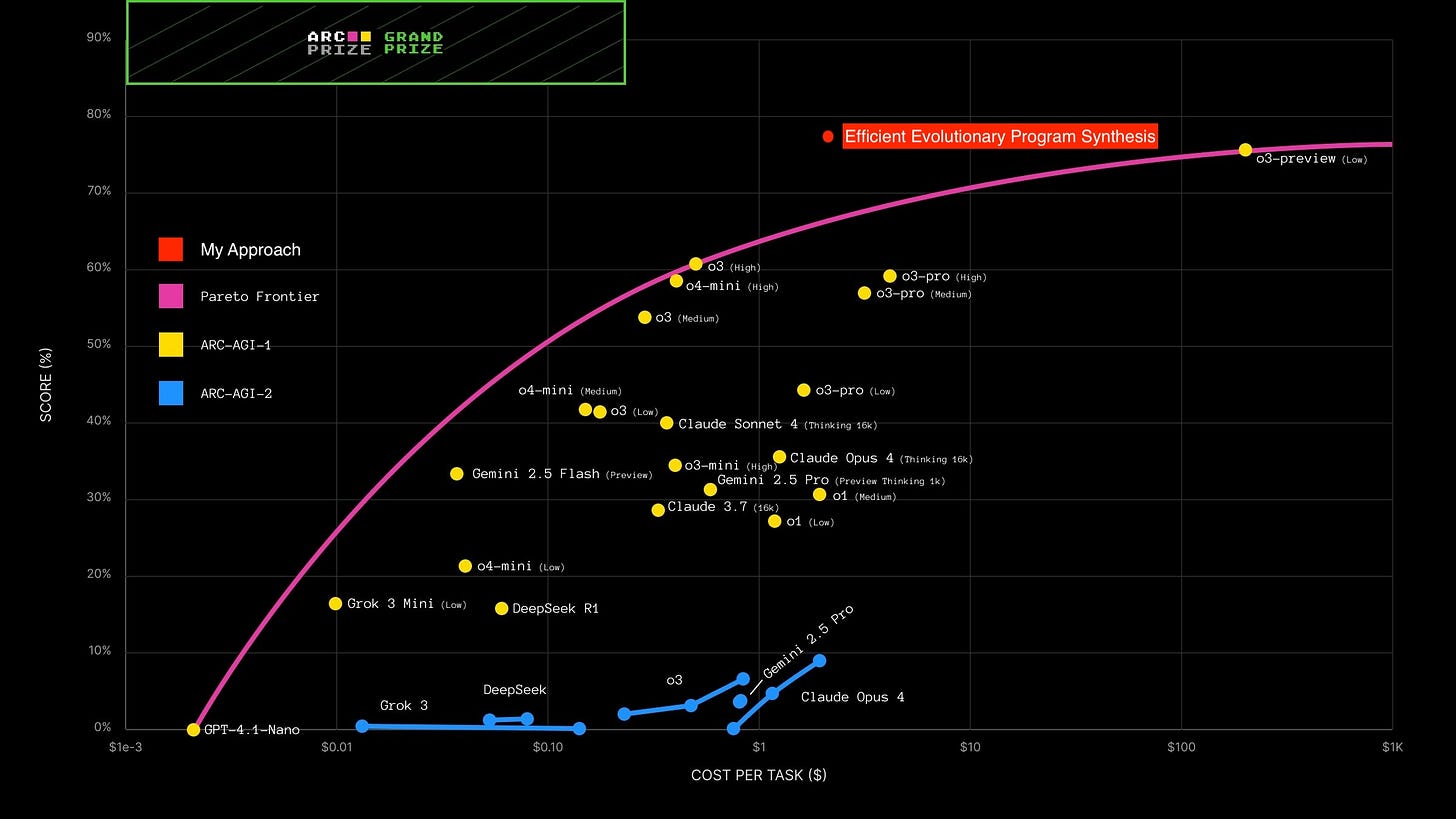

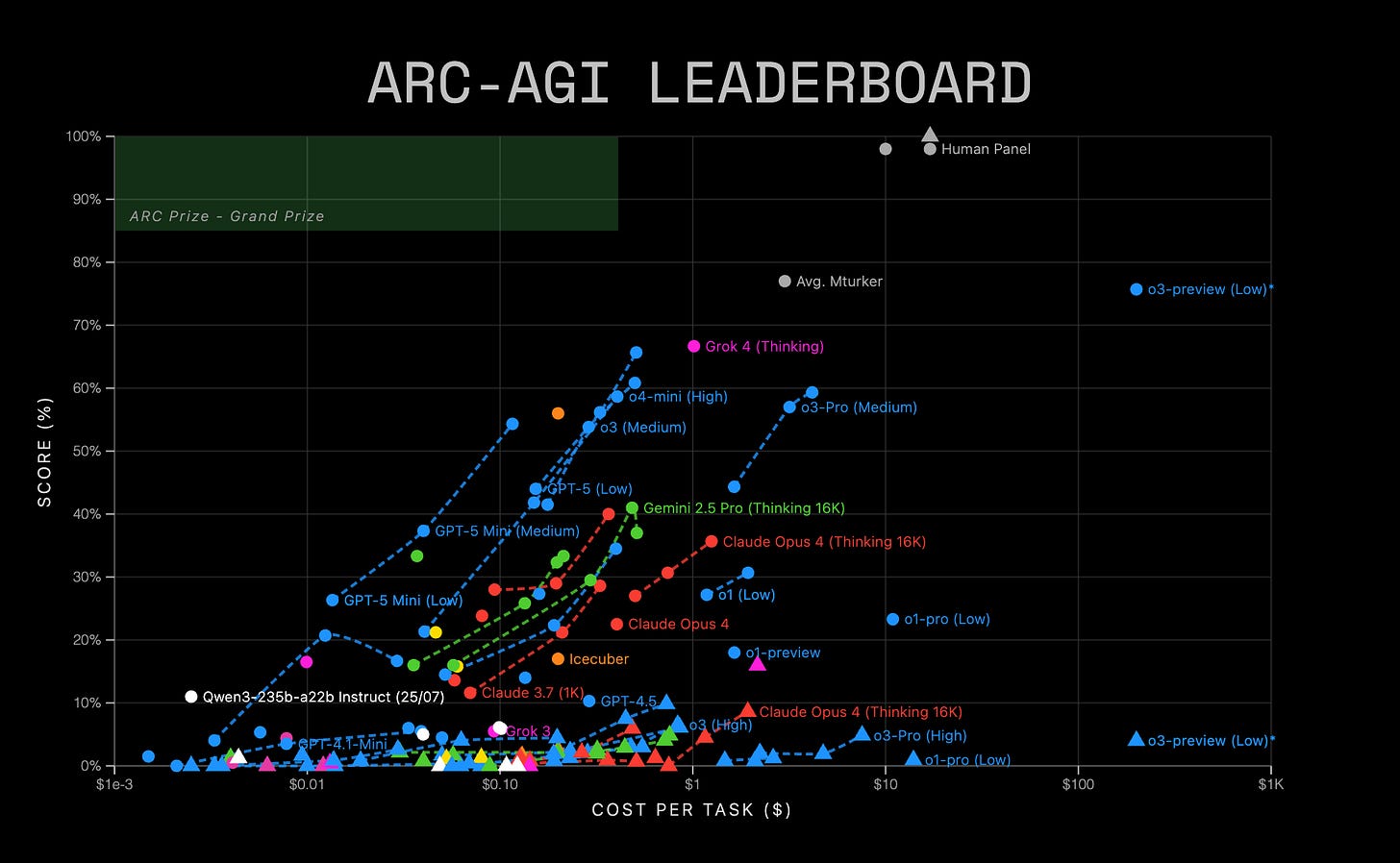

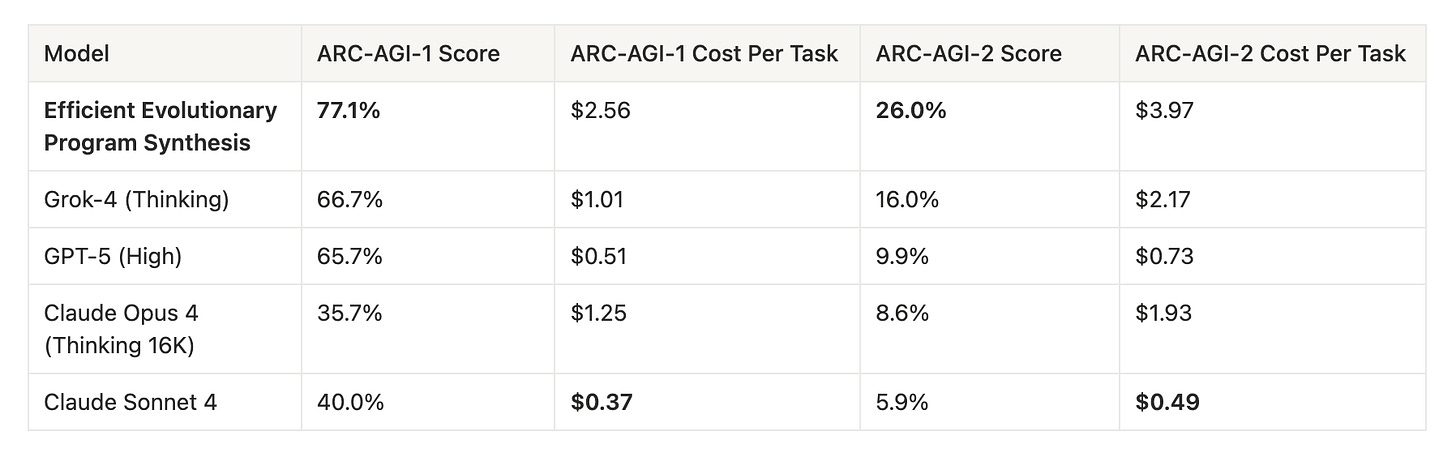

Building upon the work of Jeremy Berman, who achieved the SoTA result on the ARC-AGI-1 Public leaderboard, I designed a DreamCoder-inspired, LLM-assisted program synthesis system that can solve increasingly harder tasks by leveraging learned concepts in an expanding library of programs. My approach scored 77.1% on ARC-AGI-1 and 26.0% on ARC-AGI-2, both beating results of frontier models and previous bespoke systems [Note]. Furthermore, designed for efficiency, my system has the best performance-cost metric, breaking the existing Pareto frontier.

[Note: The ARC-Prize team let me know that Jeremy Berman has a new approach with slightly higher accuracies (2.5% higher on ARC-AGI-1 and 3.4% higher on ARC-AGI-2) that costs around 3 times more on ARC-AGI-1 and 8 times more on ARC-AGI-2. While my approach is no longer SoTA in accuracy, it’s still SoTA in terms of performance-cost efficiency. I have asked the ARC-Prize team to run my solution on a similar budget to compare the two approaches on a same cost basis.]

Table of Contents

Background

ARC-AGI

Evolutionary Test-Time Compute

DreamCoder

Motivation

My Approach

Architecture

Experiment

Result

Next Step

Acknowledgments

Background

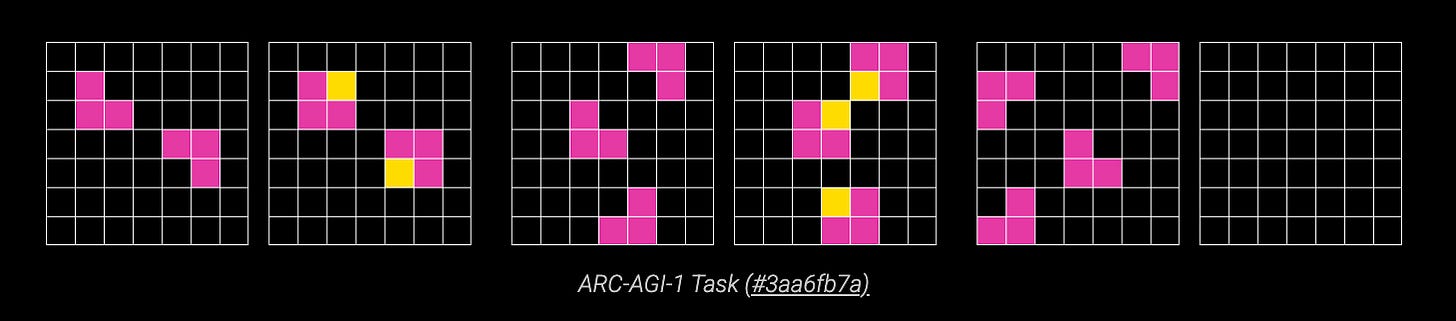

ARC-AGI

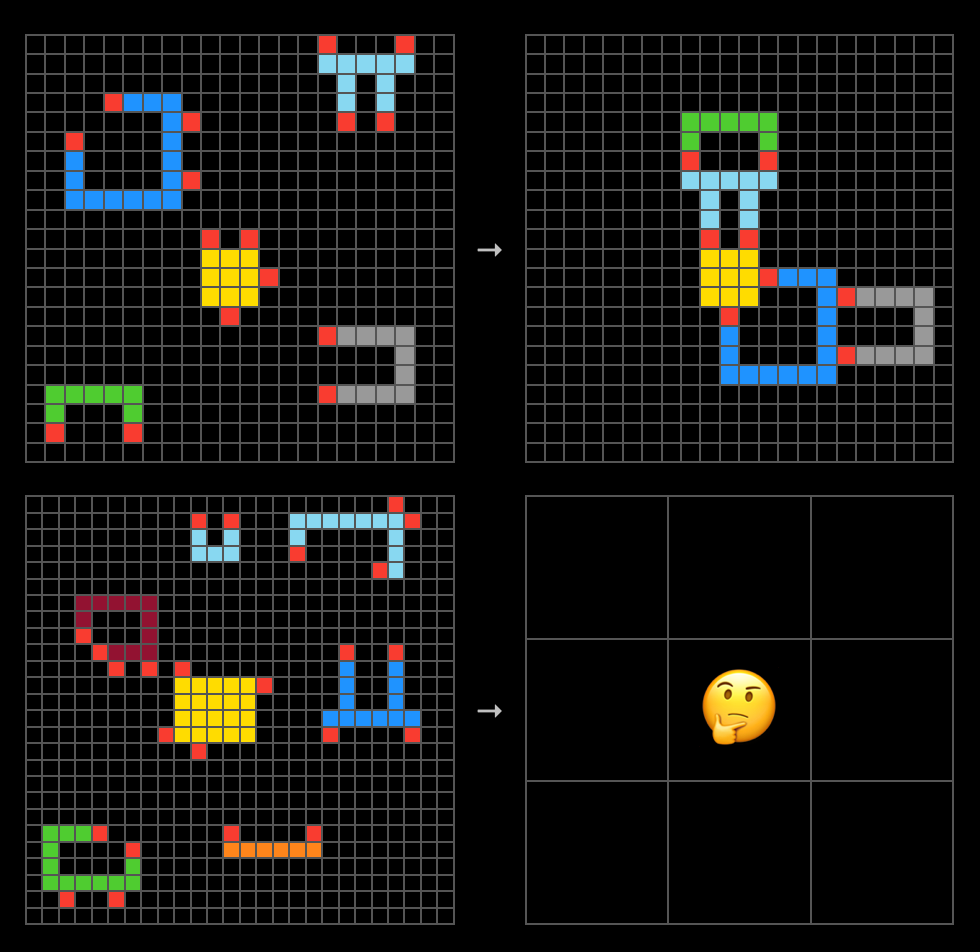

ARC-AGI is a benchmark created to measure AI intelligence, specifically on its ability to adapt to novel scenarios that it cannot solve by memorization. Each ARC task has several training examples in the form of input/output grids of colored cells which encode some unwritten rules. The goal of an AI system is discovering those rules, and then applying them to test inputs to generate output grids. An AI solves a task if all of their generated outputs are the same as the expected outputs.

ARC-AGI-2, which was launched on 25 March 2025, is the next iteration which tests more advanced AI capabilities such as symbolic interpretation (can a machine interpret symbols as having meaning beyond their visual patterns), compositional reasoning (can a machine combine multiple learned rules that interact with each other), and contextual rule application (can a machine apply rules differently based on context). It is much more difficult as evidenced by the results of frontier models: on high test-time-compute setting, Grok-4 scores 16.0% on ARC-AGI-2 vs. 66.7% on ARC-AGI-1, GPT-5 scores 9.9% vs. 65.7%, while Claude Opus 4 scores 8.6% vs. 35.7%.

ARC-AGI is famously easy for humans but hard for AI. The average human scores 77% on ARC-AGI-1, and a panel of 10 random humans achieves 98–100% on both ARC-AGI-1 and 2, much better than leading-edge models. While one model (OpenAI's o3) achieved a similar score as an average human on ARC-AGI-1, it needed to spend $200 per task to do so. Meanwhile, no models have come close to human performance on ARC-AGI-2. ARC-AGI is the one benchmark where AI models still do not saturate.

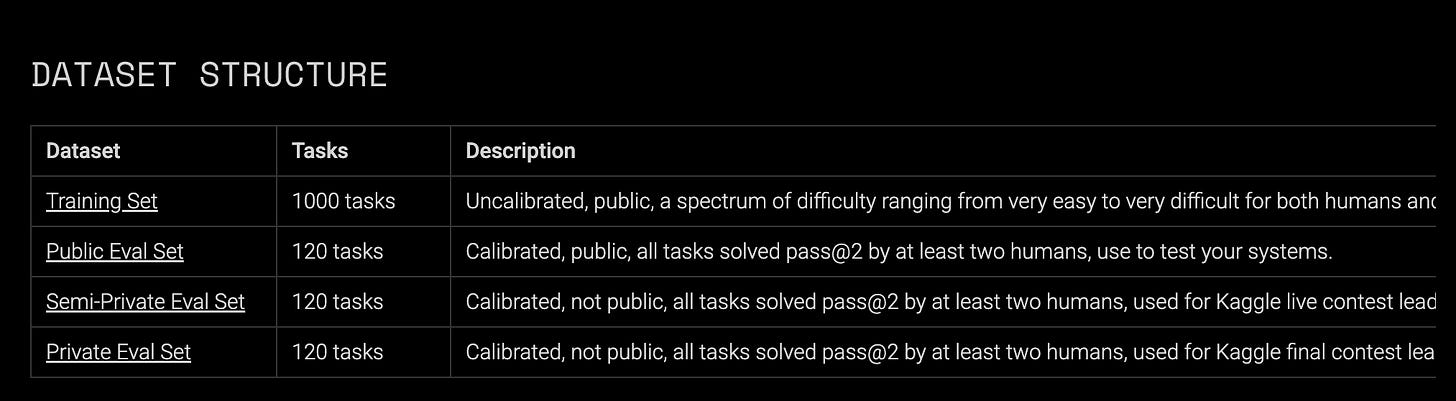

The ARC-AGI challenge has four datasets: training, public eval, semi-private eval, and private eval. The purpose of the training set is teaching Core Knowledge Priors to an AI system, whose ability can then be evaluated on the public eval set. The semi-private eval set was calibrated to have the same difficulty as the public eval set, but researchers need to coordinate with the ARC-Prize team to test their model on it in a Kaggle notebook that runs at most 12 hours. The goal is to minimize test data leakage and contamination. Finally, the private eval set is only accessible via the no-internet-access Kaggle competition and has never been exposed to third-party APIs.

The confusion about a model's performance on ARC-AGI often stems from teams reporting performance on different datasets. Unless otherwise specified, all accuracy scores in this post are evaluated on the semi-private eval set.

ARC-AGI-1 SoTA

While frontier models perform poorly on their own, ARC-AGI researchers often leverage them as part of a bespoke solution. The best performing approach for ARC-AGI-1 was Jeremy Berman's Evolutionary Test-time Compute. By "having Sonnet 3.5 generate a bunch of Python transform functions, testing them against challenge examples, and then using the best-performing functions to create new prompts for generating even better solutions," Berman achieved 53.6% accuracy on ARC-AGI-1, which was SoTA in December 2024.

This approach, together with Ryan Greenblat's AlphaCode-styled solution, validated using LLM-generated programs to tackle ARC-AGI. They showed that even though frontier models could not solve many tasks in one shot, using them to generate a large number of programs per task can improve performance. But one limitation is efficiency: Evolutionary Test-time Compute generates up to 500 python functions per task, while the number for Greenblat's system is around 8,000. Ultimately, these systems treat each ARC task as an isolated problem. When they discover a solution, they do not re-use learned concepts in the next task. But ARC-AGI specifically tests models' understanding of Core Knowledge. Once a system "learns" gravity from task A, we would want it to apply the concept in task B if task B tests projectile motion prediction. Not leveraging previously discovered concepts makes search inefficient. As compositional reasoning (combining different concepts to solve a problem) is a major criterion for ARC-AGI-2, inefficient search means these systems either cannot find the right programs or need to spend a lot of money to do so because they need to re-learn every concept for every task.

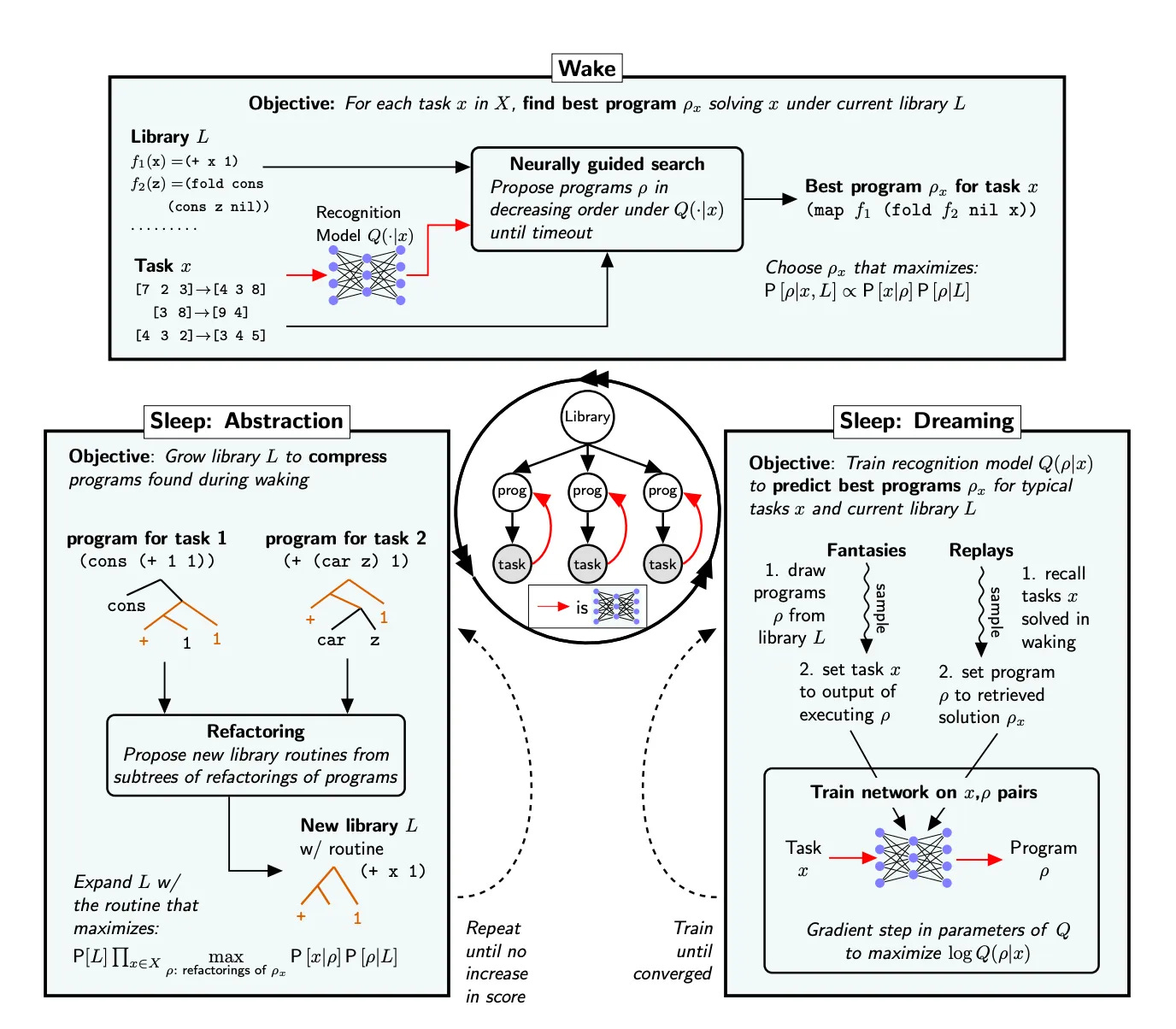

DreamCoder

While researching how to address this limitation, I came across a 2020 paper DreamCoder: Growing generalizable, interpretable knowledge with wake-sleep Bayesian program learning. DreamCoder is a neurosymbolic program synthesizer that solves tasks (defined as input/output pairs) by iteratively building up a library of programs. Starting from a library of primitives (think axiomatic functions) defined by a Domain-Specific Language (DSL), DreamCoder uses a "wake-sleep" algorithm to alternate between 1) generating programs with a neural network (recognition model) and the library to attempt tasks and 2) growing the library with more advanced programs and improving the recognition model.

DreamCoder has one stage in the Wake phase and two stages in the Sleep phase:

Wake

A neural network, called recognition model, proposes candidate programs based on current library and task.

Sleep: Abstraction

Expand the library with more advanced functions based on solution programs found during waking

Refactor programs to abstract out common components. The resulted routine is added to the library if it minimizes the description length of the library plus the description lengths of the refactoring

Sleep: Dreaming

Train the recognition model to predict the best programs p_x for tasks x with the updated library via Fantasies and Replays

Fantasies: Sample programs p from the current library. For a task x, update x_output to be p(x_input). Train the recognition model such that p has a better chance to be surfaced for task (x_input, p(x_input)).

Replays: Recall tasks x solved during waking and set p_x to be the solution program found. Train the recognition model such that p_x has a better chance to be surfaced for task x.

DreamCoder has been tried in the ARC-AGI challenge before by Mikel Bober-Irizar and Soumya Banerjee. They handcrafted 77 primitives for their Perceptual Abstraction & Reasoning Language (PeARL) and scored 4.5% on the ARC-AGI-1 public eval set.

Motivation

Evolutionary Test-time Compute and DreamCoder have opposite strengths and weaknesses.

Evolutionary Test-time Compute

Strength:

Scalable. LLMs can generate an arbitrary number of diverse and valid programs.

Weakness:

Knowledge learned from one task is not transferred to another.

DreamCoder

Strength:

Library of programs keeps evolving and is used across tasks.

Weakness:

Programs are polymorphically typed λ-calculus expressions, which are not Turing-complete. The set of programs it can generate is smaller and less diverse than an LLM.

Handcrafted DSL means a lot of human engineering is required to get started. This is concerning in two ways. First, human intelligence is embedded into how the language is designed. If a system performs well on a task, it's unclear if the system is generalizing or the solution is already encoded in the DSL choice. In addition, handcrafted systems run contrary to the bitter lesson.

I decided to combine these two ideas: using LLMs to generate programs in Python (a Turing-complete language), growing system expertise by adding promising programs to a library, and including the current best program from the library in the LLM prompt to search for a better solution.

My Approach

Architecture

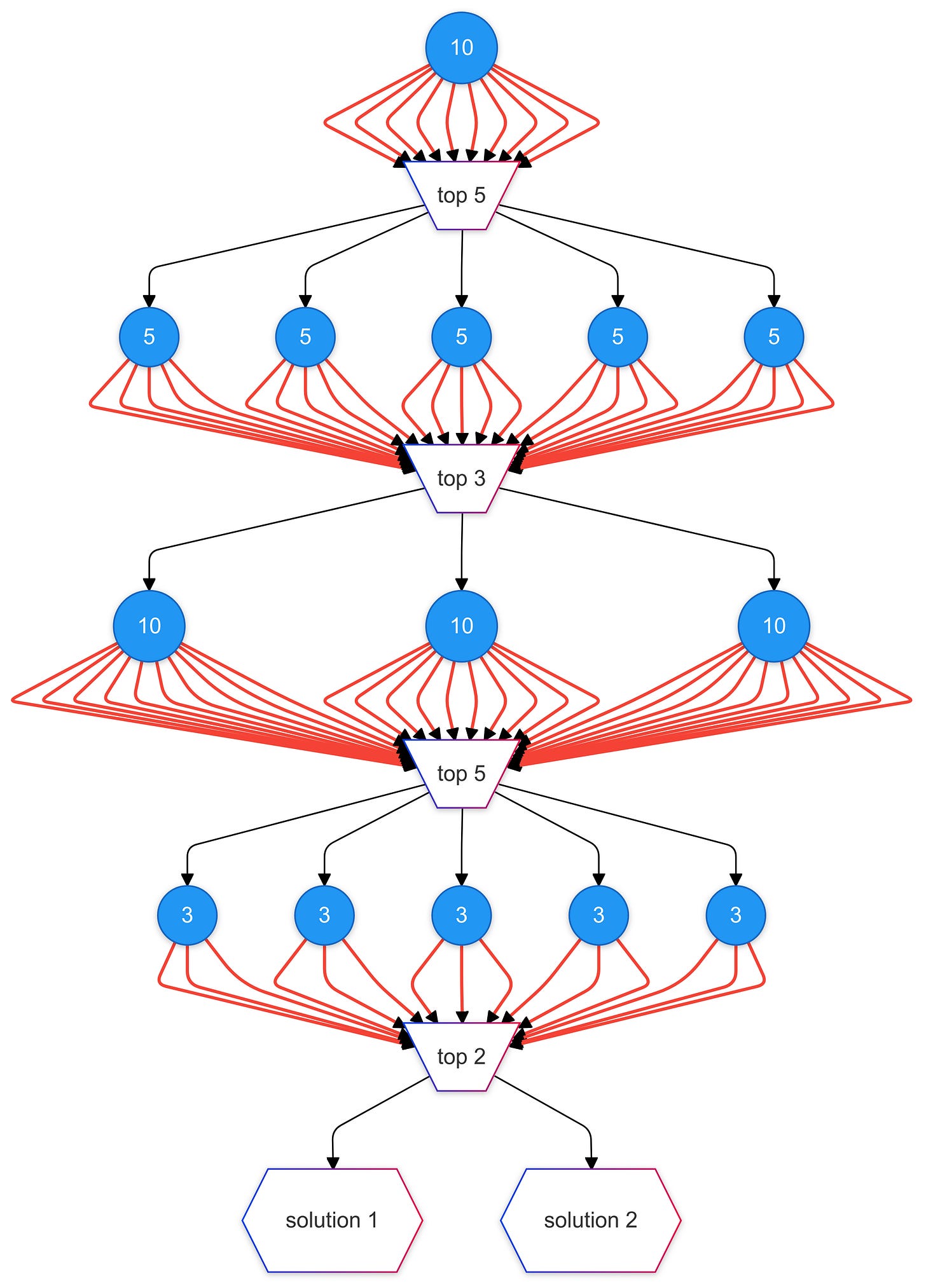

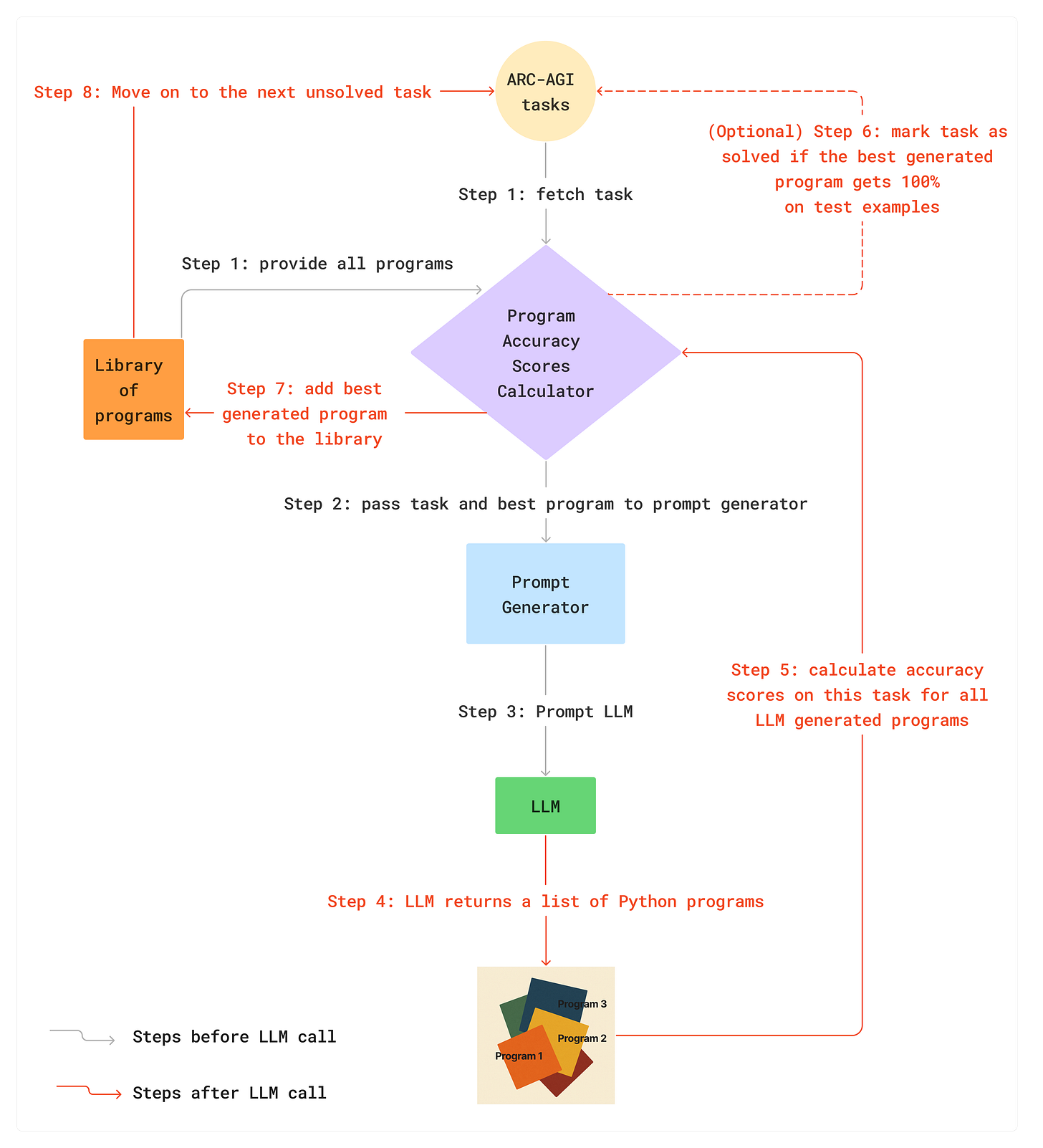

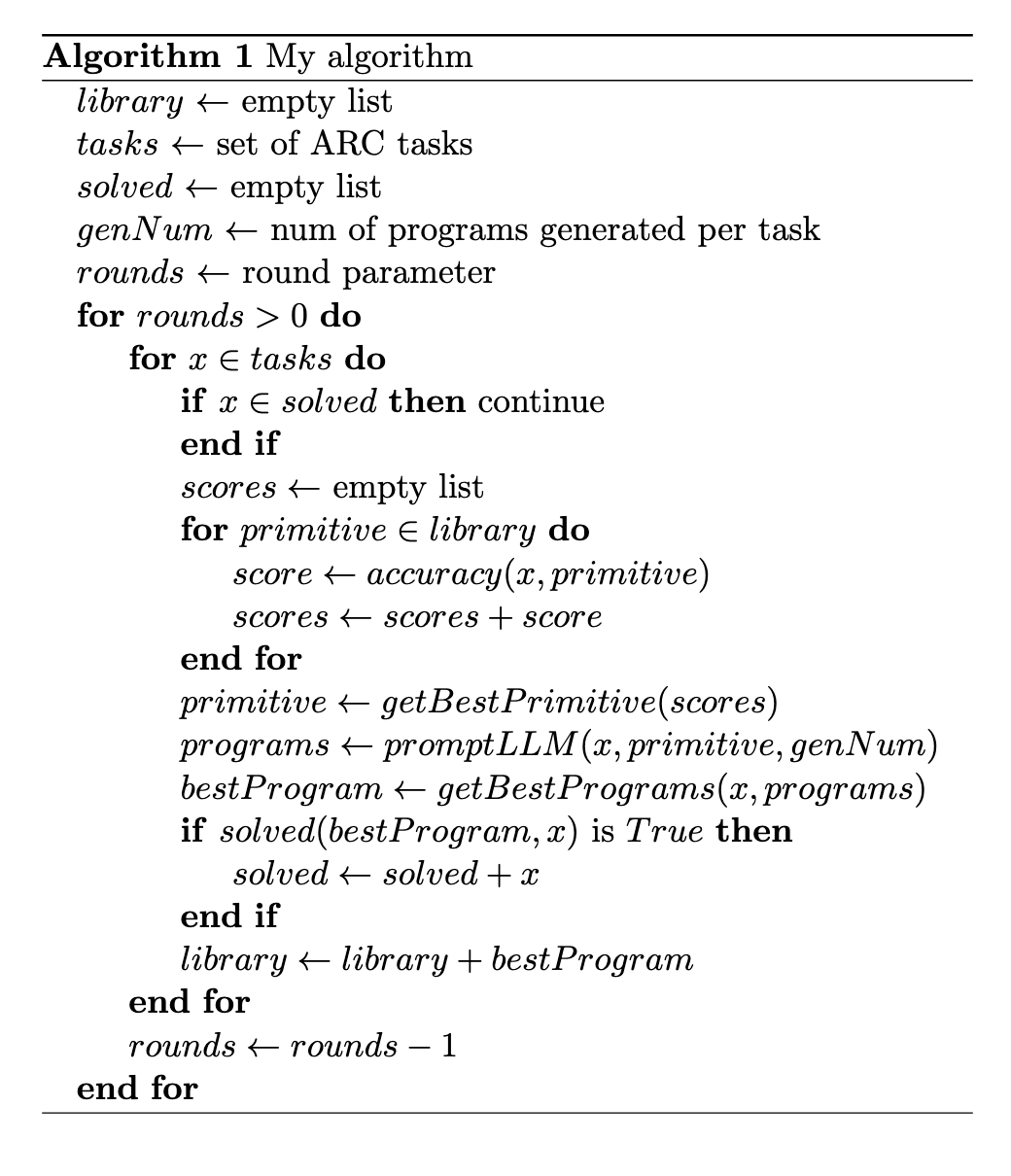

Starting from an empty library, my system loops through each task to prompt an LLM for Python program(s) that can solve all of the training examples. I used the same prompt as Jeremy Berman and Ryan Greenblat which requires the LLM to perform Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning. Each input/output grid is represented in multiple formats, namely grid dimensions, Base64 image encoding, ASCII and Python nested list. One addition I made is including in the prompt the current best program in the library. My system computes a primary accuracy score (how many correct training examples) and a secondary accuracy score (average cell-level accuracy on the training examples) for every program in the library on the task, and includes the best one in the prompt (first sort by primary score; tie-break by secondary score).

Out of all programs returned by the LLM, the one with the best primary and secondary accuracy scores is added to the library. The system then moves on to the next task with an expanded library until all tasks have been attempted once. The system then either starts from the first task again or ends, depending on the user-provided rounds parameter.

Notice there are several differences between my approach and DreamCoder:

DSL choice: instead of handcrafting primitives, my library is originally empty. No need for human engineering to get started.

Recognition model: recall the recognition model has two responsibilities in DreamCoder: identifying useful programs from the library and composing candidate programs.

identifying useful programs from the library: my system uses accuracy scores heuristics. I also tried using a neural network and got promising results, but ultimately didn’t use it in the final system because of Kaggle runtime constraints. More on this in Next Step.

composing candidate programs: use LLM

Sleep (Abstraction): instead of adding functions to the library by refactoring common components of found solutions during waking, the most promising program returned by the LLM is added to the library.

Sleep (Dreaming): recognition model is now part heuristics score and part LLM. This stage is skipped because no model weights have to be updated

Experiment

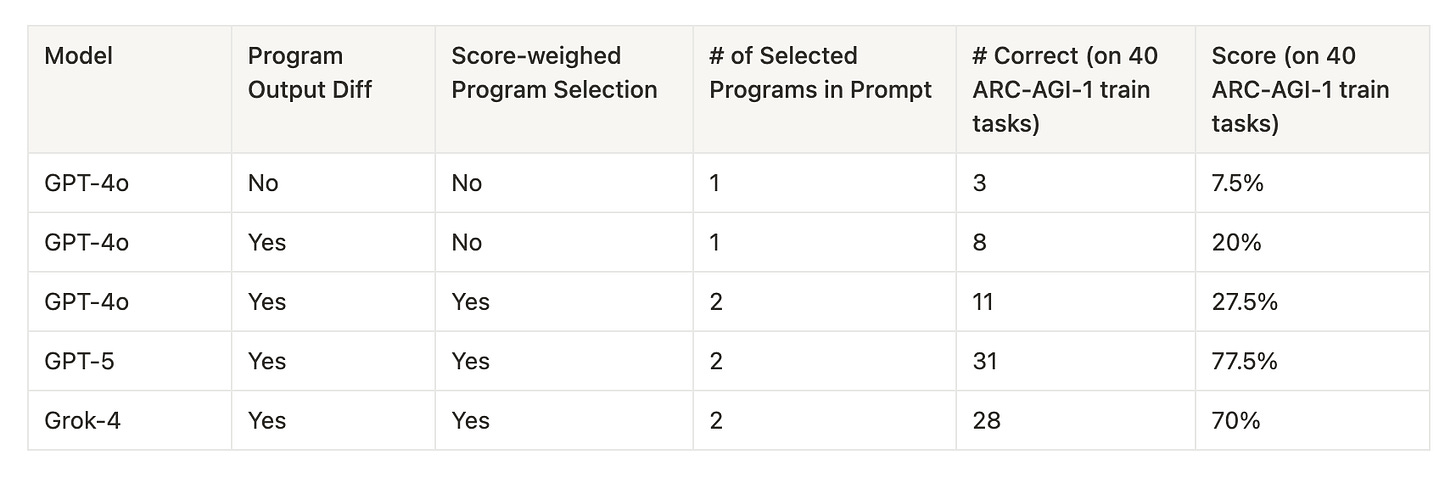

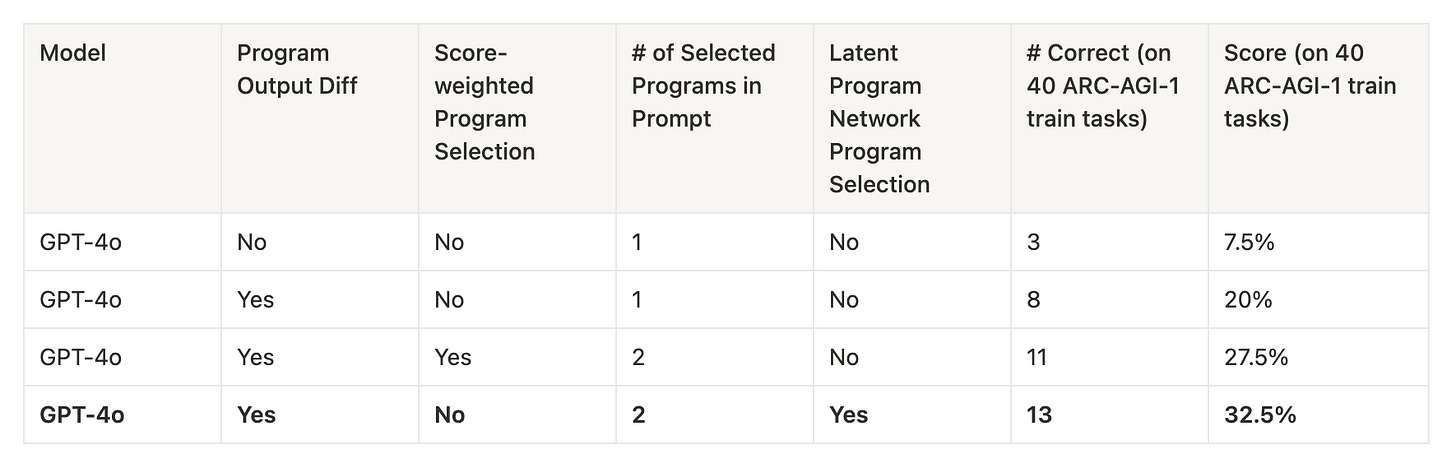

I experimented with LLM choice, prompt format, and program selection heuristics on 40 randomly selected ARC-AGI-1 training tasks. The system ran for five rounds with the LLM generating one program per task in each round.

Model: the most recent generation of models (GPT-5 and Grok-4) are much better.

Program Output Difference: whether to include failed training examples and the difference between expected outputs and actual outputs in the prompt. Experiments showed including this information significantly improves performance. Providing more context is almost always better.

Score-weighted Program Selection: instead of sorting library programs first by primary accuracy score and then by secondary accuracy score for program selection, I tried summing the two scores, converting the sums into probabilities using softmax, and then sampling programs. Exploration is encouraged since the program with the best scores would not always be used.

Number of Selected Programs in Prompt: how many programs to be selected from the library.

Based on the experiments and Grok-4's outperformance on the leaderboard, I decided to use Grok-4 with program output difference, score-weighted program selection, and two selected programs in the prompt for the final submission run.

Result

In order to teach the system Core Knowledge, I first ran it on the ARC-AGI-2 public training set of 1,000 tasks with parameters of 1 round and 1 program generated per task in a round. This training seeded the library with 538 programs (note: this is fewer than 1,000 because the API sometimes timed out or returned invalid programs). Next, the system was run on the semi-private set for 2 rounds. In each round, 5 programs were generated per task.

My system outperformed the frontier models on both ARC-AGI-1 and 2. While frontier models cost less per task, my system is more efficient and breaks the performance-cost Pareto frontier. Also, my approach only requires 10 LLM calls per task compared to Berman's 500 and Greenblat's 8,000 with a better accuracy on ARC-AGI-1. One caveat is they used the last generation of models (Claude Sonnet 3.5 and GPT-4o respectively) while I used Grok-4. Using GPT-4o's $0.05 and Claude Sonnet 3.7's $0.058 cost per task on the ARC-AGI-1 leaderboard (which should be an underestimation since their prompts are more comprehensive; Claude Sonnet 3.7 costs the same as Sonnet 3.5), the estimated cost per task of Berman's and Greenblat's solutions was $29 and $400 respectively, while mine was $2.56 on ARC-AGI-1.

Next Step

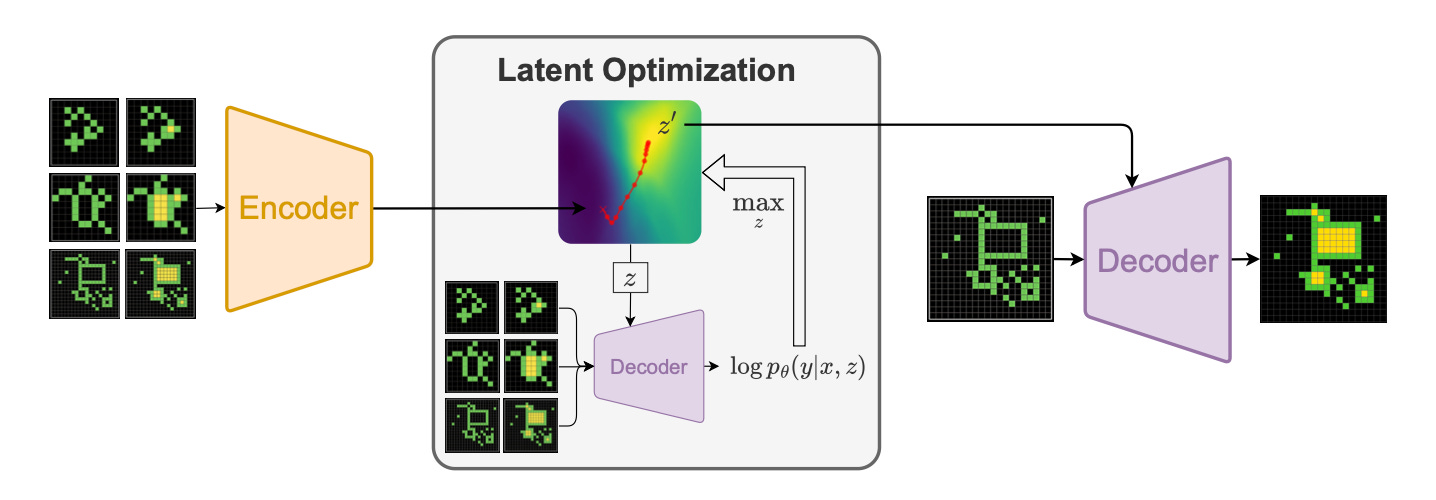

I experimented with using a neural network to find the best programs in the library for LLM to evolve. The neural network is based on Searching Latent Program Spaces by Clément Bonnet and Matthew V. Macfarlane.

One of the 2024 ARC-AGI-1 Paper Award winners, this paper introduced Latent Program Network (LPN), a Variational Autoencoder-styled model with the learned latent space representing a searchable space of ARC-AGI programs. Using training examples as inputs to the encoder, each ARC-AGI task is mapped to a latent vector z in a space of encoded programs. The system then performs "latent optimization via gradient ascent": by feeding z and input grids of training examples to the decoder to generate predicted output grids, a differentiable loss w.r.t. z is computed by comparing decoder outputs to actual outputs. The gradient is then used to optimize z. Finally, the optimized z and test input(s) are provided to the decoder to generate model's prediction of test output(s).

I tried using LPN to replace the accuracy score heuristics in the recognition model. For each ARC-AGI task, I first mapped it to an optimized latent vector z via gradient ascent. This vector represents the idealized program for this task which we want to find the symbolic representation for. Next, I applied each program in the current library to the training example input grids to get the program outputs. These new input/output pairs were then fed to the LPN encoder, with the resulting latent vector also optimized. Now we obtained one program latent for each Python program in the library. Finally, the cosine similarities of the expected latent z and each program latent were converted to probabilities using softmax. Library programs were then sampled for LLM to evolve. The intuition is that comparing programs in the latent space can capture nuances not available in cell-by-cell comparisons in accuracy score heuristics.

Applying LPN in program selection was promising but the resulting system took longer than the 12-hour allowed runtime on Kaggle and hence was not part of my final submission. Nonetheless, it shows the promise of neural-guided program synthesis and is something I want to explore further.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Jeremy Berman and Ryan Greenblat for open-sourcing their code and SoTA approaches for me to build upon, the DreamCoder team for designing an elegant program synthesis system, Clément Bonnet and Matthew V. Macfarlane for their work on Latent Program Network, François Chollet and Mike Knoop for co-founding ARC prize, and Greg Kamradt for helping to test my solution.

I also want to acknowledge the similarities between my approach and Google DeepMind's AlphaEvolve: both use LLM to generate more advanced programs to expand a library. While I came up with the idea independently (here's my first commit on 8 May 2025 while AlphaEvolve was published on 14 May 2025), their approach of marking components to evolve instead of evolving whole programs and using dynamic prompts and ensemble LLMs is very interesting. These ideas could potentially improve my system.

My code is open-sourced! Check out https://github.com/epang080516/arc_agi

Eric, really nice work and very clearly written. And very cost efficient!

A few Qs, if you don’t mind.

Did you test any text-only models (like OSS 20B)? I notice all three models you tested were multi-modal and am wondering how important that is.

In the “Score-weighed program selection” column, does “No” mean you sampled uniformly (at random), while “Yes” means you greedily take the highest train accuracy, using pixel match as a tie breaker?

In the library generation phase, you did one round. Was that also 5 programs per task there?

I suppose you have to execute the whole library on every task so that you get the scoring, correct? Should be quick, but does that become a bottleneck?

The score is determined first by train accuracy and then by pixel accuracy. I assume that train accuracy is nearly always zero for the first round on a given task, so that means pixel accuracy must be doing all of the heavy lifting?

Are you already working on ARC-AGI-3?